- Home

- Thurston Clarke

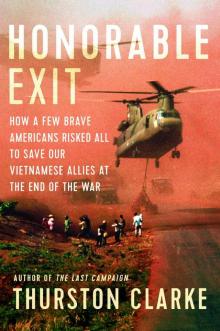

Honorable Exit

Honorable Exit Read online

Also by Thurston Clarke

JFK’s Last Hundred Days

The Last Campaign

Ask Not

Searching for Crusoe

California Fault

Pearl Harbor Ghosts

Equator

Thirteen O’Clock

Lost Hero

By Blood and Fire

The Last Caravan

Dirty Money

Copyright © 2019 by Thurston Clarke

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Map designed by Jeffrey L. Ward

Cover design by Emily Mahon

Cover photograph © Dirck Halstead/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Clarke, Thurston, author.

Title: Honorable exit : how a few brave Americans risked all to save our Vietnamese allies at the end of the war / Thurston Clarke.

Other titles: How a few brave Americans risked all to save our Vietnamese allies at the end of the war

Description: First edition. | New York : Doubleday, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018029232 (print) | LCCN 2018042953 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385539654 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385539647 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Vietnam War, 1961–1975—Evacuation of civilians—Vietnam (Republic) | Vietnam War, 1961–1975—Campaigns. | Vietnam War, 1961–1975—Diplomatic history. | Vietnam (Republic)—Foreign relations—United States. | United States—Foreign relations—Vietnam (Republic)

Classification: LCC DS557.7 (ebook) | LCC DS557.7 .C53 2019 (print) | DDC 959.704/31—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018029232

Ebook ISBN 9780385539654

v5.4_r1

ep

FOR TOM GILLILAND AND BEN WEIR

Contents

Cover

Also by Thurston Clarke

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

South Vietnam—1975

Principal Characters

Prologue: The Man in the White Shirt

Chapter 1: Omens

Chapter 2: Walter Martindale’s Convoy

Chapter 3: Who Lost Vietnam?

Chapter 4: Designated Fall Guy

Chapter 5: “I’d Tell the President That!”

Chapter 6: “In the Shadow of a Corkscrew”

Chapter 7: Palpable Fear

Chapter 8: Operation Babylift

Chapter 9: “People Are Going to Feel Badly”

Chapter 10: “No Guarantees!”

Chapter 11: Playing God

Chapter 12: “Godspeed”

Chapter 13: “Make It Happen!”

Chapter 14: “I Won’t Go for That”

Chapter 15: Kissinger’s Cable

Chapter 16: Richard Armitage’s Courageous Silence

Chapter 17: Eighteen Optimistic Minutes

Chapter 18: Frequent Wind

Chapter 19: Ken Moorefield’s Odyssey

Chapter 20: Into the South China Sea

Chapter 21: The 420

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Illustration Credits

Illustrations

About the Author

South Vietnam—April 1975

Principal Characters

WASHINGTON, D.C.

PRESIDENT GERALD FORD

HENRY KISSINGER: secretary of state and national security adviser

JAMES SCHLESINGER: secretary of defense

BRENT SCOWCROFT: National Security Council deputy adviser

DAVID KENNERLY: President Ford’s personal photographer

KENNETH QUINN: National Security Council staff member

CRAIG JOHNSTONE and LIONEL ROSENBLATT: Foreign Service officers who return to Saigon to rescue their Vietnamese friends

SOUTH VIETNAM

State Department

GRAHAM MARTIN: U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam

WOLFGANG LEHMANN: deputy chief of mission

DON HAYS: Foreign Service officer whom Martin expels from South Vietnam

JOE MCBRIDE: Foreign Service officer

FRANCIS TERRY MCNAMARA: consul general in Can Tho

WALTER MARTINDALE: Foreign Service officer in Quang Duc province

KEN MOOREFIELD: Foreign Service officer, former special assistant to Ambassador Martin

THERESA TULL: acting consul general in Da Nang

Defense Attaché Office

MAJOR GENERAL HOMER SMITH: U.S. defense attaché

BRIGADIER GENERAL RICHARD BAUGHN: deputy defense attaché

ANDREW GEMBARA: plainclothes military intelligence officer at Defense Attaché Office

Department of Defense and U.S. Military

ERICH VON MARBOD: deputy assistant secretary of defense

RICHARD ARMITAGE: former naval officer with extensive experience in South Vietnam

COLONEL AL GRAY: Marine Corps officer in charge of the ground security force at Tan Son Nhut on April 29

LIEUTENANT GENERAL RICHARD CAREY: commander of the Ninth Marine Amphibious Brigade

U.S. Delegation to the Four-Party Joint Military Team

COLONEL JOHN MADISON: head of U.S. delegation

LIEUTENANT COLONEL HARRY SUMMERS

CAPTAIN STUART HERRINGTON

SPECIALIST 7 GARRETT “BILL” BELL

Central Intelligence Agency

THOMAS POLGAR: Saigon chief of station

JAMES DELANEY: base chief in Can Tho

O. B. HARNAGE: U.S. embassy deputy air operations officer

JAMES PARKER: CIA agent in the Mekong delta

National Security Agency

TOM GLENN: senior NSA official in South Vietnam

Civilians

MARIUS BURKE: pilot who helps prepare rooftop helipads in Saigon

ED DALY: president of World Airways

BRIAN ELLIS: CBS Saigon bureau chief

ROSS MEADOR: program director for Friends of the Children of Vietnam

BILL RYDER: deputy chief of the U.S. Military Sealift Command

AL TOPPING: Pan Am station manager

Prologue: The Man in the White Shirt

On the afternoon of April 29, 1975, Dutch photojournalist Hubert “Hugh” Van Es looked out the window at the United Press International (UPI) office in downtown Saigon and saw a helicopter landing on an elevator shaft rising from the roof of 22 Gia Long Street. Van Es grabbed his camera and a 300 mm lens and hurried onto the balcony. As a man in a white shirt was reaching down to help a person at the top of a staircase board the helicopter, Van Es took the last g

reat iconic photograph of the Vietnam War. A UPI editor in Tokyo misidentified the building as the American embassy, and despite later corrections the mistake has survived in books, in articles, and on the internet, perhaps because placing the helicopter on the roof of the embassy makes the photograph a more potent symbol for America’s first lost war.

Compare the Van Es photograph with the even more iconic one that Associated Press (AP) reporter Joe Rosenthal shot of six U.S. servicemen raising an American flag on the summit of Mount Suribachi during the World War II battle for Iwo Jima. Both were taken near the end of a war, and both show Americans framed against an open sky—reaching up to plant a flag or down to grab a refugee. Otherwise, they seem to have nothing in common. One symbolizes victory in a war Americans have spent decades celebrating; the other, defeat in a war they have spent decades trying to forget. One represents courage and sacrifice; the other, catastrophe and disgrace. But the more one learns about the staircase on the roof of 22 Gia Long Street, the people standing on it, the pilots of that helicopter, and the man in the white shirt, the more apparent it becomes that Van Es had also memorialized a moment of stirring heroism.

He later described the 22 Gia Long Street stairway as a “makeshift wooden ladder.” But zoom in from a different angle and with a stronger lens, as French photojournalist Philippe Buffon did that same afternoon, and it becomes a sturdy staircase wide enough to be climbed by four people abreast. Zoom in some more and the helicopter becomes a Bell Huey 205 painted in the blue and white livery of Air America, one of the CIA’s proprietary airlines, and you can see that the man in the white shirt has a seven-day beard, a black patch over his left eye, and a cigar clenched in his teeth and that his shirt is ripped and filthy. Patrons of Saigon’s rowdier bars would recognize him as Oren Bartholomew “O. B.” Harnage, the U.S. embassy’s deputy air operations officer and a middle-aged roustabout described by one friend as “a gregarious, macho good old boy, a bull-shitter of the first order…[and] suds-sipper of renown.” The cigar was one of the seven that Harnage smoked daily, perhaps as an homage to his father, a Tampa cigar roller who had abandoned him at birth, in either 1925 or 1926—he was uncertain which. He had volunteered for the navy at seventeen (or eighteen) and been wounded on Okinawa. A sliver of old shrapnel had worked its way into his left eye the previous month, explaining the patch. He had joined the air force after the war, moved to the CIA as a contract employee, and after seven years in Laos and Vietnam had concluded that America had been “naïve” to involve itself in the Vietnam War.

Earlier that afternoon CIA chief of station Thomas Polgar had asked him to commandeer one of the Air America helicopters that had been landing on the embassy roof and direct its pilots to 22 Gia Long Street to evacuate a group of Polgar’s personal friends and senior South Vietnamese officials. Risking his life to rescue some dignitaries rubbed Harnage the wrong way. He decided instead to board everyone, he explained later, “first come, first served…ladies and infants being the exception.” After landing on the Gia Long Street roof, he punched out a burly Korean diplomat (a Polgar VIP) who had elbowed the other evacuees aside, and threw large suitcases—some heavy with gold bars—off the roof. Parents handed him their children before climbing back down the stairs in tears. Notes pinned to the children’s shirts read, “My son wants to be a doctor,” and “My daughter is very musical.”

Van Es photographed Harnage as he was leaning down to grab Dr. Thiet-Tan Nguyen, a young military doctor who would become an anesthesiologist in Southern California. Next he grabbed Dr. Tong Huyhn, who would practice family medicine in a suburb of Atlanta. Next came Tuyet-Dong Bui, a slender teenage girl who will call herself Janet at the California university where she will earn a degree in microbiology before becoming a biotech researcher. Hours before, a stray bullet had killed one of her high school classmates, and her mother had urged her to leave. Her brother, who stood a rung below her, had traded his motorbike to the chauffeur of a high-ranking military officer in exchange for being led here. Standing below him was a Polgar VIP, Minister of Defense Tran Van Don, who had recently told South Vietnamese troops, “In the coming hours, in the coming days, I will be by your side.”

Elevator shafts like the one at 22 Gia Long Street usually have a rudimentary iron or wood ladder so mechanics can climb up and service their machinery. Yet no one seeing the Van Es photograph appears to have asked why such a large and sturdy staircase happened to be leading to the top of the elevator shaft—in effect, leading nowhere. It was there because on April 6 Marine Corps colonel Al Gray had flown over downtown Saigon in a helicopter, surveying the roofs of buildings leased by U.S. government agencies. Air America pilots Marius Burke and Nikki Fillipi had then inspected the roofs that Gray believed capable of supporting a helicopter, gauging their strength and checking for obstructions. After choosing the thirteen most promising ones, they had supervised a crew of American contractors who rerouted electrical and telephone cables and removed flagpoles and washing lines. The contractors custom built two staircases for 22 Gia Long Street: a short one leading from the main roof to an intermediate platform, and a longer one connecting that platform to the top of the elevator shaft. Their staircases had handrails and short steps so that children and the disabled could climb them.

Major General Homer Smith, the U.S. defense attaché and senior military officer in South Vietnam, approved Burke and Fillipi’s preparations, but Ambassador Graham Martin was furious when he learned about their makeshift helipads. He believed that any indication that the United States was preparing an evacuation would demoralize South Vietnam’s military, undermine the government of President Nguyen Van Thieu, and lead to revenge attacks on American civilians. He refused Burke’s request to pre-position barrels of fuel on the roofs, park helicopters on them overnight, and paint an H in green Day-Glo paint on them that matched the dimensions of a Huey’s skids so that Air America pilots could see which ones had been converted to helipads and where to align their skids to ensure a 360-degree clearance. Martin argued that the H might alarm the Vietnamese washerwomen who dried laundry on the roofs. On his own building’s roof, Burke painted the outline of an H in green dots that he later connected. Other Air America pilots ignored Martin and painted a green H on other helipads.

Bob Caron and Jack Hunter piloted the helicopter that landed on 22 Gia Long Street. They were among the thirty-one middle-aged Air America pilots who had volunteered to make these hazardous flights. Before Harnage recruited them to rescue Polgar’s VIPs, they had been setting down wherever they saw people standing on a roof with an H. Caron was a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran who, like Harnage, did not give a hoot if the people he collected from these roofs were high or low priority, government ministers or their chauffeurs. He was rescuing them, he said, “to preserve America’s honor.” By the time Van Es took his iconic photograph, Caron and Hunter had made three pickups from Gia Long Street. Each time they lifted off, Caron shouted to the people being left behind on the stairs, “We’ll make as many runs as we can!”

A Huey could carry twelve combat-loaded American soldiers, but because Vietnamese are smaller and many of the evacuees were women and children, Harnage packed twenty people onto every flight. To make more room, he rode outside, standing on a skid while holding a Swedish machine gun in one hand. A passenger gripped his other arm to prevent him from falling to his death in case he was hit by ground fire from North Vietnamese troops or disgruntled South Vietnamese soldiers. (Earlier that day, while stopping at Tan Son Nhut to transfer his passengers onto one of the larger Marine Corps helicopters that were shuttling out to the U.S. fleet, Caron had noticed a bullet hole in his drive shaft.) Harnage had suffered wounds on Okinawa while fighting for his country and his comrades; on April 29, he was risking his life to turn a few more Vietnamese strangers into American citizens.

Van Es had captured Caron’s last pickup from Gia Long Street. Caron was almost out of gas and would have to fly half an

hour out to the U.S. Navy fleet to refuel. As he lifted off for the last time, he met the eyes of those he was leaving behind—people who were unlikely to become doctors, musicians, biotech researchers, or anything else in the United States and might instead be among the hundreds of thousands of “class enemies” that the Communists would send to a gulag of “reeducation” camps. Some would be incarcerated for as long as seventeen years, unless they died first from malnutrition, disease, hard labor, and mistreatment. It was in their eyes, Caron thought, that “you could see they knew we were never coming back.” Harnage never forgot their “pleading eyes” and would remember his last flight from Gia Long Street as a “nightmare” of people “waiting on a ladder for a helicopter that does not return.” All across Saigon on April 29, Americans avoided Vietnamese eyes. As a group walked down a boulevard toward an evacuation bus, passing Vietnamese watching silently from the doorways of their homes and shops, one man kept saying, “Don’t look in their eyes….Don’t look in their eyes….Don’t look in their eyes.” A reporter who had refused to help her Vietnamese translator and his family escape, telling herself they would be “better off” in Saigon, never forgot “the look of supplication in the eyes of his wife and children.” Decades later, an American diplomat remained haunted by “the look in the eyes of those I had to leave behind.”

Honorable Exit

Honorable Exit JFK's Last Hundred Days: The Transformation of a Man and the Emergence of a Great President

JFK's Last Hundred Days: The Transformation of a Man and the Emergence of a Great President